Longtime water quality expert shares proof of Iowa’s progress

Author

Published

4/19/2022

The evidence is literally etched into Iowa’s landscape:

- Terraces (to stop erosion and nutrient runoff) span more than 90,000 miles, longer than all of the streams in Iowa, combined.

- Grassed waterways (to keep soil and nutrients in fields) cover 300,000 acres.

- And 250,000 water and sediment control basins trap runoff before it can reach nearby water bodies.

Looking at these numbers alone, it’s clear that conservation has been a priority on Iowa’s farms for quite some time.

But are these decades-old conservation practices (and others like them) producing current results? And what do they say about farmers’ ability and willingness to take on the latest challenges related to water quality?

For those answers, you need someone like Shawn Richmond – a water quality expert with a master’s degree in Water Resources and 25 years of experience across academia (Iowa State University), government (Iowa Department of Agriculture and Land Stewardship), and the private sector (Iowa Nutrient Research and Education Council). Earlier this year, Shawn joined the Iowa Farm Bureau, as our Conservation and Natural Resources Policy Advisor.

Are Iowa’s existing conservation practices producing results?

As mentioned, Iowa’s farmers have been cutting soil erosion (and the phosphorus runoff that goes along with it) for decades, using terraces, grassed waterways, water and sediment control basins, conservation tillage, no-till and more. In fact, Iowa farmers lead the nation in conservation tillage and no-till acres.

“When you drive across Iowa or fly over and see the waterways, terraces and other conservation signatures on Iowa’s landscape, it’s evident that there’s been a large amount of work for a very long time,” says Shawn.

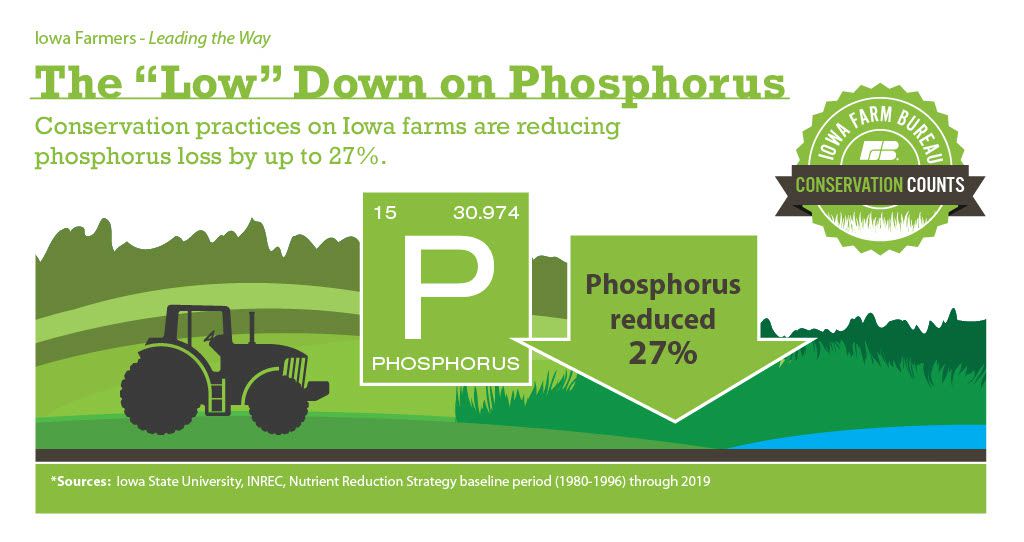

According to Shawn and data from the Iowa Nutrient Research and Education Council (INREC), those on-farm practices have reduced phosphorus losses from fields by up to 27% since the 1980s. To put that number into perspective, Iowa’s goal (through the Nutrient Reduction Strategy) is for agriculture to reduce its phosphorus losses by 29%. So, when it comes to phosphorus, Iowa’s farmers are already close to meeting their goal, and they’re on a trajectory to exceed it soon.

How are farmers adapting to take on Iowa’s latest water quality challenges?

A decade ago, the State of Iowa developed a collaborative, science-based plan to conserve the state’s soil and protect our water from nutrients like phosphorus and nitrate. That strategy (the Nutrient Reduction Strategy) was developed by researchers at Iowa State University, the Iowa Department of Agriculture and Land Stewardship (IDALS), and the Iowa DNR.

Shawn Richmond was working for IDALS at that time, and he played an instrumental role in putting the strategy together.

In addition to existing conservation efforts, the strategy called on farmers to adopt a suite of new practices, specifically designed to address nitrate losses.

Farmers responded.

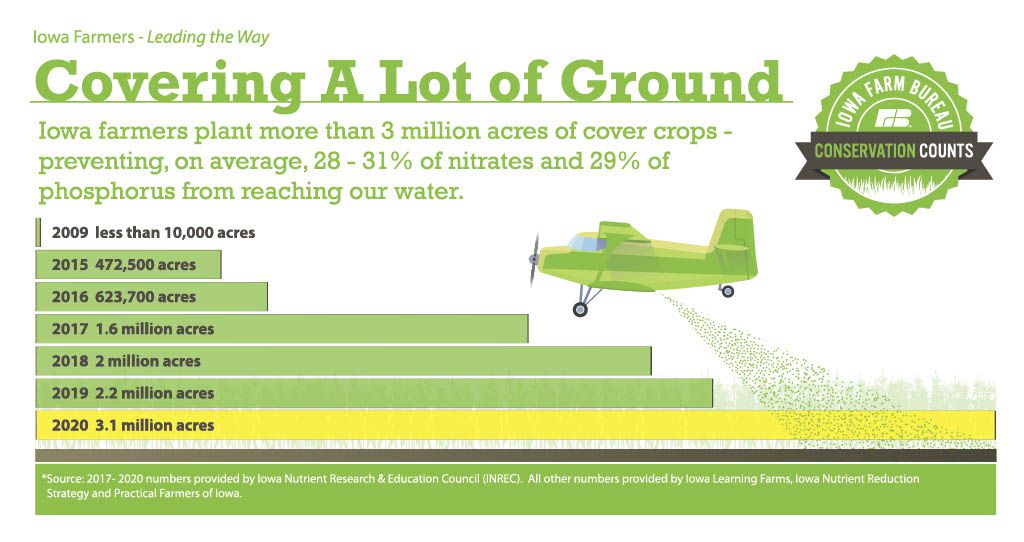

“We’ve seen farmers be really quick to adopt many of these [nitrate-reducing] practices,” says Shawn. “Some evidence of that is the dramatic increase we’ve seen in cover crops. In the 2020 crop year, INREC data shows Iowa had more than 3 million acres of cover crops. Comparing that number to a decade ago – when we probably had less than 10,000 acres – shows the dramatic scale up and adoption that’s happened from field to field and county to county.”

Cover crops are just one example. Recent “blitz” projects are helping farmers scale up other nitrate-specific practices, like wetlands, bioreactors, saturated buffers, and more. For instance:

- 57 new water quality wetlands are currently under development in priority watersheds across the state.

- In 2021 alone, 40 saturated buffers and 11 bioreactors were added to Polk and Dallas County fields through a unique public/private partnership, and the partners leading that initiative plan to add 80-100 more of those practices in 2022.

- In February, partners in six eastern Iowa counties announced plans to add 60 edge-of-field water quality practices (including bioreactors and saturated buffers) this year.

- And the City of Ames and Story County recently announced that they plan to install 25 edge-of-field water quality practices (including saturated buffers and bioreactors) by the end of 2022.

In addition to making changes in their fields, farmers are also making significant changes to the way they apply fertilizer to their fields. Precision agriculture technology is helping farmers spoon-feed their plants a precise amount of fertilizer at the right time and in the right place. Farmers are even using technology that helps the fertilizer stay where it belongs.

“Nutrient management practices have come a long way to help minimize nitrogen losses,” says Shawn. “Technologies like nitrification inhibitors – some of these were virtually non-existent in the 1970s and 1980s. Today, they’re common practice, with over 80% of fall anhydrous applications using nitrification inhibitors to help stabilize nitrogen and prevent nitrate loss.”

Why should Iowans be confident in Iowa’s water quality future?

In addition to the progress that’s been demonstrated so far, Shawn points to the collaboration, innovation, and dedicated, long-term funding aimed at water quality protection.

Remember – back in 2013 Shawn was at IDALS, helping launch the Nutrient Reduction Strategy and getting it off the ground with just a handful of demonstration projects around the state.

The growth in projects and collaboration since then has been remarkable. Cities (like Cedar Rapids and Des Moines), government agencies, farmers, private organizations, and others are working together toward the common goal of conservation and water quality improvement.

“Nowadays you can’t throw a rock without hitting a conservation or watershed project or some type of conservation partnership,” says Shawn. “Really, they’re everywhere across the state, in everyone’s backyard.”

As those conservation partnerships have developed, so has the technology that farmers employ to protect the soil and water.

“Some of these are relatively new conservation practices,” says Shawn. “CREP wetlands and bioreactors weren’t around long before the Nutrient Reduction Strategy was put in place. And since the strategy was released a decade ago, new innovative practices have been added to the mix, like saturated buffers and multi-purpose oxbow wetlands. This shows that we’re not just happy with the status quo. We’re continuing to work on new tools and implement them across the state.”

Couple those factors with significant support by lawmakers, and you can understand the optimism that’s been rippling through farm country.

“We’ve really seen new and unprecedented levels of dedicated long-term sustainable funding in Iowa, focused on conservation and water quality,” says Shawn – referring to Senate File 512, a 2018 bill that initiated long-term dedicated funding to implement Iowa’s Nutrient Reduction Strategy. In 2021, the Iowa legislature and Governor acted again, extending the timeline for that dedicated funding to 2039.

The successes of the past thirty years (addressing erosion and phosphorus) have given us a model to replicate and adapt to Iowa’s current water quality issues. But this time, we’re taking on the challenge with stronger partnerships, better technology, more precise measurement, and reliable funding – four factors that give water quality veterans like Shawn confidence in Iowa’s future.

“Bottom line: What I see is that we have had results in the past, and that we’re definitely on the path to producing more results moving forward.”

By Zach Bader. Zach is Iowa Farm Bureau’s Digital Marketing Manager.

Hear more from Shawn Richmond (Iowa Farm Bureau’s Conservation and Natural Resources Policy Advisor) in this week’s edition of The Spokesman Speaks podcast.

Want more news on this topic? Farm Bureau members may subscribe for a free email news service, featuring the farm and rural topics that interest them most!