HPAI, Layer Inventories, and Egg Prices

Author

Published

8/1/2022

HPAI, Layer Inventories, and Egg Prices

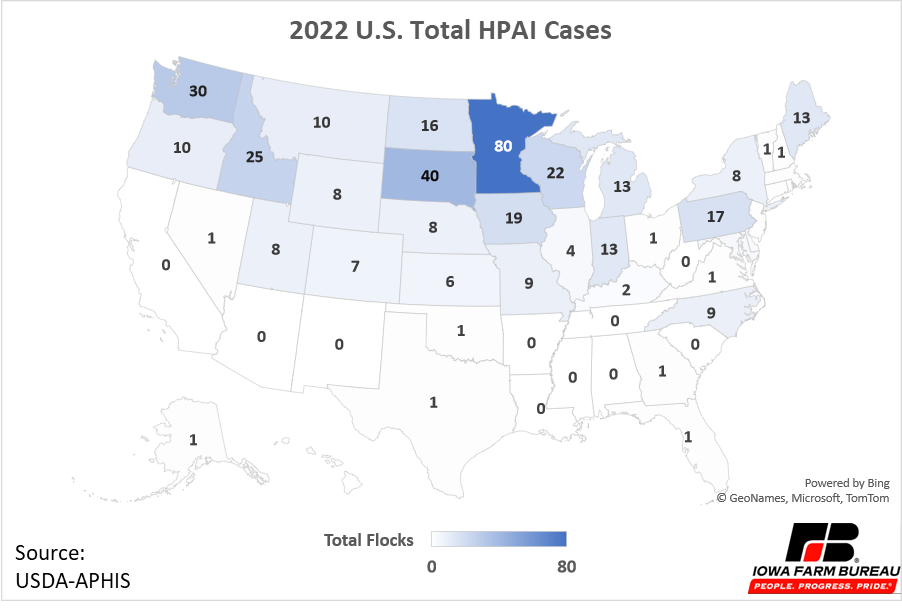

On February 9, 2022, the USDA announced confirmation of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI) in Indiana. On March 7, 2022, HPIA was confirmed in Iowa. This was the beginning of the first major HPAI outbreak since 2015. In 2015, 50 million birds in 211 commercial flocks and 21 backyard flocks across 15 different states were affected by HPAI. So far in 2022, 40 million birds in 188 commercial flocks and 209 backyard flocks across 38 states have been affected by HPAI. Total 2022 HPAI cases by state are shown in Figure 1. The outbreak brought reduced egg production and increased egg prices as layers were culled to stop the spread of the disease.

Figure 1. 2022 U.S. Total HPAI Cases

A signal that the HPAI outbreak may be nearing an end came on Thursday, July 21, 2022, as the Iowa Department of Land Stewardship reported the last commercial flock was released from HPAI quarantine restrictions after clearing all testing protocols and quarantine requirements. The quarantine restrictions prohibited the movement of all poultry and poultry products on or off the affected premises. Iowa has not had a commercial case since April and has had no cases since May when one backyard case was confirmed. Iowa has 13% of all U.S. layers and is the number one egg producing state in the U.S. Of the 40 million birds in the U.S. that have been affected by HPAI in 2022, 13 million were in Iowa. This includes all poultry (chickens, turkeys, other poultry), not just laying hens.

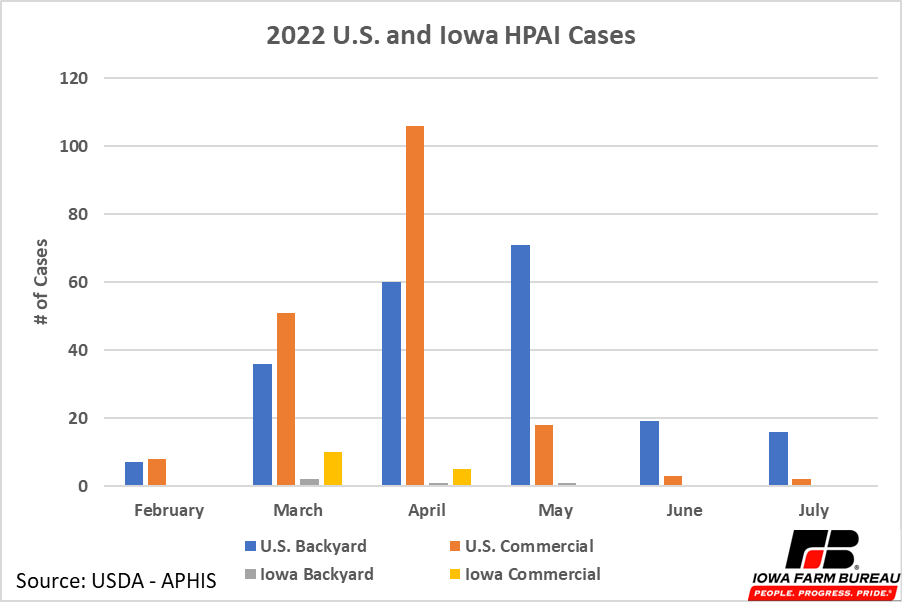

HPAI cases have been decreasing across the U.S. Over the last two months only five new cases of HPAI have been confirmed in commercial flocks across the U.S. (Figure 2). Backyard flocks still had a total of 35 confirmed cases over the past two months but backyard flocks represent a small percentage of the total poultry population and new cases have been declining in backyard flocks as well.

Figure 2. 2022 U.S. and Iowa HPAI Cases

As the 2022 outbreak nears an end, the reaction of the industry after the 2015 outbreak can give us an idea of how production and prices may react in the coming months. This article specifically looks at the egg industry.

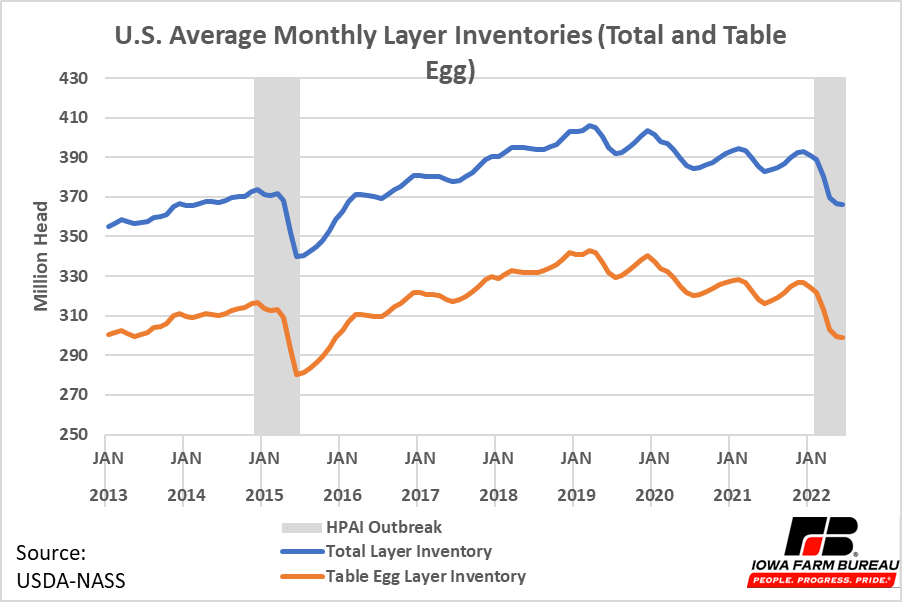

Figure 3 shows U.S. average monthly layer inventories. Table egg inventory includes only hens laying eggs to be consumed while total layer inventory also includes hens laying eggs to be hatched for chicks. U.S layer inventories bottomed out in June 2015, near the end of the 2015 outbreak. Table egg layer inventories fell around 30 million head, from an average of 311 million head in the 12 months prior to the outbreak to a low of 280 million head. From the low in June 2015, it took nine months for inventories to return to 310 million head in March 2016.

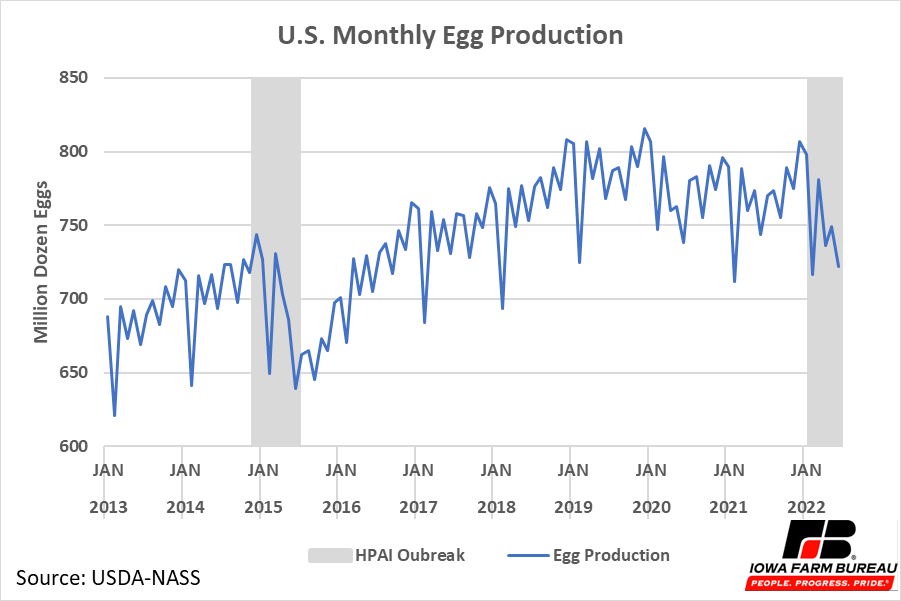

As expected, egg production followed layer inventories during the 2015 outbreak. Figure 4 shows U.S. monthly egg production. Normal dips in monthly egg production occur every February as it is the shortest month of the year. U.S. egg production can average as high as 26 million dozen per day. A drop of 3 days from 31 days to 28 days in February can swing monthly egg production around 75 million dozen for the month. February drops are not as drastic in 2016 and 2020 as those were leap years. Ignoring the February dips, monthly egg production significantly decreased near the end of the 2015 outbreak. Egg production declined approximately 60 million dozen per month, from an average of 707 million dozen per month in the 12 months prior to the outbreak to a low of 639 million dozen per month. Production returned to pre-outbreak levels in March 2016, around the same time layer inventories recovered.

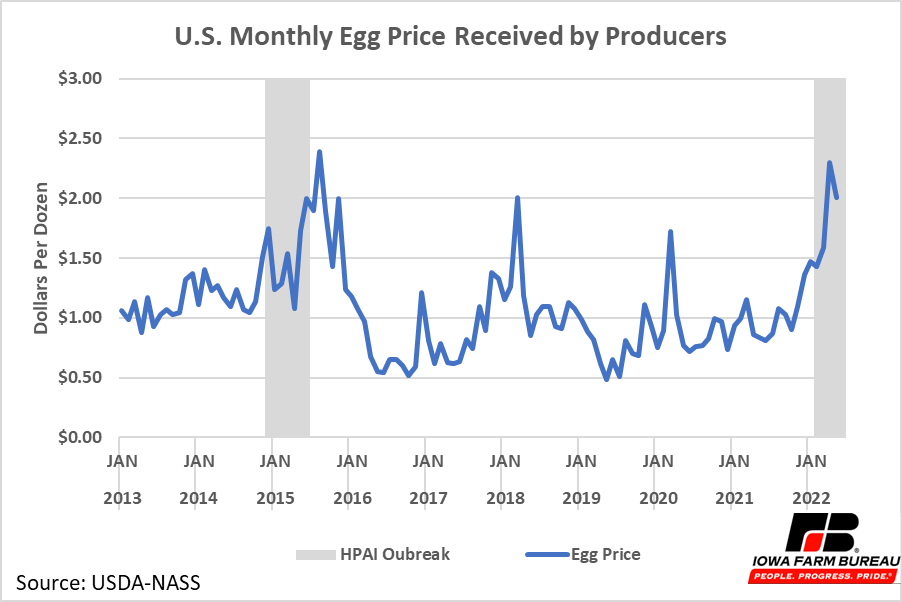

As supplies of eggs decreased, prices received by producers increased. Producers received an average of $1.23 per dozen in the 12 months prior to the 2015 outbreak. During and immediately following the outbreak prices were generally higher except for a few months. Prices peaked at $2.39 per dozen in August of 2015 (Figure 5). This was an increase of $1.16 per dozen from the average price received in the twelve months prior to the 2015 outbreak. Prices returned to pre-outbreak levels in December of 2015, four months after the price high in August 2015. Notably, prices returned to pre-outbreak levels faster than layer inventories and egg production after the 2015 outbreak. One explanation is increased egg prices caused some consumers to stop purchasing eggs for a short period of time, temporarily decreasing demand and some commercial egg users (bakeries and processed food producers) found substitutes for egg products in their recipes.

After the 2015 outbreak, inventories and production increased to levels higher than those seen prior to the outbreak. Increased supply sent prices lower than those seen prior to the outbreak. Price spikes occurred in 2018 due to especially strong consumer demand and in 2020 due to supply chain disruption issues created by the COVID-19 pandemic. Other than those instances, egg prices typically remained between $0.50 and $1.00 from 2016 to the beginning of the 2022 outbreak.

During the 2022 outbreak, layer hen inventories, egg production, and egg prices have followed a similar pattern to those of the 2015 outbreak up to this point. During the 2022 outbreak table egg layer inventories fell around 23 million head, from averaging 322 million head in the 12 months prior to the outbreak to low of 299 million head (Figure 3). This resembles the decrease of 30 million head during the 2015 outbreak. Similarly, egg production fell by approximately 50 million dozen per month, from averaging 771 million dozen in the 12 months prior to the outbreak to a low of 722 million dozen (Figure 4). This is comparable to the 60 million dozen per month drop during the 2015 outbreak.

The comparison of prices received by producers in the 2015 and 2022 outbreaks is a little tougher to make. Increased feed costs and inflation have likely influenced prices in addition to the 2022 HPAI outbreak. Egg prices were climbing prior to the detection of HPAI in February 2022 (Figure 5). Prices were close to $1.50 per dozen in January 2022. Prices continues to climb to a high of $2.30 per dozen in April 2022, the same month that confirmations of HPAI peaked. Using January 2022 as a starting point, this represents an $0.80 per dozen increase, which is comparable to the $1.15 per dozen increase during the 2015 outbreak. It is important to note that some of the $0.80 per dozen increase could have been caused by sharply rising feed costs and high levels of inflation in the general economy, not HPAI. Therefore, a recovery from HPAI may not remove all of the $0.80 per dozen increase.

As the 2022 outbreak comes to an end, several factors could influence the recovery of layer inventories and future egg production and prices. If inventories and prices recover at a rate similar to the rate experienced following the 2015 outbreak, inventories and prices could return to levels seen prior to the 2022 outbreak in nine months. However, persistent high feed costs and record high inflation currently facing the industry were not present during the 2015 recovery process and could cause the 2022 recovery process to take longer than expected.

Figure 3. U.S. Average Monthly Layer Inventories (Total and Table Egg)

Figure 4. U.S. Monthly Egg Production

Figure 5. U.S. Monthly Egg Price Received by Producers

Economic analysis provided by Aaron Gerdts, Research Analyst, Decision Innovation Solutions on behalf of Iowa Farm Bureau.

Want more news on this topic? Farm Bureau members may subscribe for a free email news service, featuring the farm and rural topics that interest them most!